Interview in Usbek & Rica

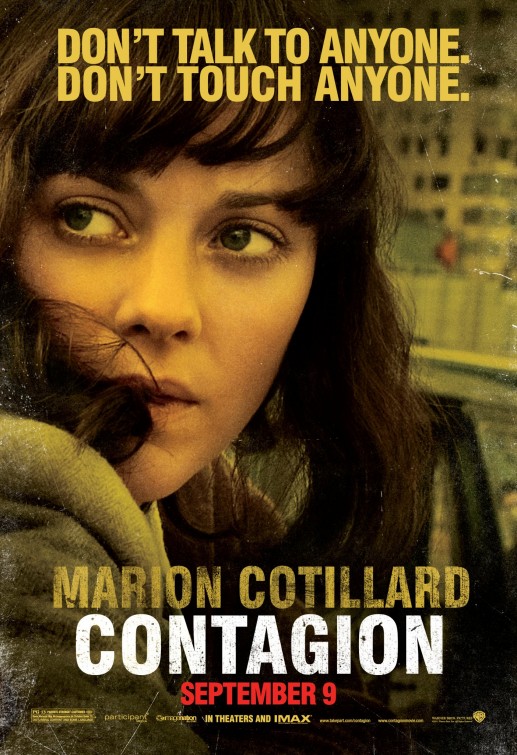

I was interviewed by the French publication Usbek & Rica, along with Colin Tait, my co-author on The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh, about the Coronavirus and the film Contagion. The French version is available here and our original English responses are below:

Revisiting Contagion in the context of the current coronavirus pandemic, what strikes you the most about it?

Andrew: Watching Contagion in the midst of the coronavirus, it’s one of those surreal experiences of a societal-cinematic feedback loop, not unlike 9/11. When it feels like we’re living through an apocalyptic movie, we seek solace in apocalyptic movies, which in turn influences our perception of the “real-life” situation. Unlike most end-of-days movies, though, Contagion is noticeably lacking in exaggerated spectacle. There is no need for hyperbole; the disease is enough. The film barely adds any melodrama, letting the virus rip through the thin veneer we call civilization.

Colin: What strikes me now is how misinformation is as deadly as the virus itself. As Jude Law’s character exploits the crisis for personal and financial gain, he taps into the overall current of public distrust for the establishment, which only exacerbates the situation. I think Craig Mazin’s Chernobyl series is a great companion piece to Contagion, as it demonstrates, in painstaking detail, how the lies of the official powers set the preconditions for the disaster to erupt and how a culture that values toadyism – rather than the competence of experts – is a disaster waiting to happen. In the United States, we definitely find ourselves in a similar situation.

A number of news outlets have recently described the movie as “prophetic”. Do you agree with this? If so, how exactly is the movie prophetic, according to your understanding? In particular, you just mentioned that “at the time, the film’s depiction of online misinformation was considered far-fetched”. What do you mean by that?

Andrew: I think there are a number of ways we can see Contagion as prophetic. At its most basic, the film takes the premise of what a pandemic would look like in a fast-paced, globalized world. In 2011, when the film was released, the H1N1 “swine flu” pandemic had swept across the world just two years previous; Contagion imagines a quicker, deadlier pandemic and aims to portray it as realistically as possible. The film’s chief science advisor was Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, Professor of Epidemiology at Columbia, who worked with the screenwriter to model a virus and the CDC’s response. This attention to realism, rare for a Hollywood thriller, is perhaps the first layer of the film’s prophetic nature: the film seems to have accurately predicted what a pandemic would look and feel like in part because the filmmaking team, especially Soderbergh, writer Scott Z. Burns, and Dr. Lipkin, put in the work. Beyond its accuracy, however, the more intriguing aspect of the film’s prescience is its portrayal of rapid societal decay. This is a common thematic for films about any kind of outbreak or assault, whether it’s disease or war or zombies: humanity’s capacity to cooperate, or lack thereof. The Night of the Living Dead, after all, is less about zombies than it is about a small group of people too petty and dysfunctional to defend themselves from a group of slow-moving corpses. Contagion, similarly, shifts its focus in the second half of the film toward the human response to a pandemic. Violence breaks out quickly, bureaucrats bicker over costs, military officers seek geopolitical influence, hedge funds aim to profit off market shifts, and other instances of greed, selfishness, and cruelty demonstrate that the real villain of the film is not actually the virus, but shameful aspects of human nature. Unfortunately, our current experience with the coronavirus is proving the film prophetic in this regard as well. Finally, one aspect of the film that many critics at the time took issue with was Jude Law’s character, Alan Krumwiede, a conspiracy theorist and blogger who casts doubts on the CDC’s reporting on and handling of the pandemic. At the time, the character was thought of as a far-fetched caricature, a cheap shot at the culture of blogging. Nine years of social-media fueled misinformation later, this aspect of the film rings more true than ever. If the film was written today, Alan Krumwiede would have a primetime show on Fox News.

What can you say about Contagion’s production development? With this movie in particular, did you notice any major differences regarding the way Steven Soderbergh worked, compared to his other movies?

Colin: Soderbergh has remarked that he actually cut more than 40 minutes from the movie. This is pretty consistent with his overall editing technique, where he shoots all day, and edits at night on his computer. His use of the RED-One camera, a high-definition digital camera capable of achieving film-like quality, at the time was revolutionary, whereas now it is standard practice. Since he is also the cinematographer, Soderbergh is able to film with an eye to cutting the scenes down in advance which uniquely equips him to film with very little coverage. I think that this cutting style is also what defines the film’s clinical edge and tone, where viewers are only given the bare minimum of information, and only know what they are supposed to. Soderbergh’s editing style allows for what I call “the hidden flashback” — a signature reveal in the very last seconds of the narrative and reorders everything that the viewer knows about what they just saw. Without spoiling too much about the movie, it is almost as if there is a little part of the story that Soderbergh keeps in his pocket and then, when we have settled into our conventional ordering of it, he pulls it out like a magician and changes our perspective entirely.

Screenwriter Scott Z. Burns just spoke out about Contagion. Regarding the fact that the story is not told through the eyes of one character but through a community of characters, he says that his inspiration came from 1970s disaster films and the value of “an ensemble cast when you’re trying to tell far-flung stories, so there’s always someone onscreen who the audience is really interested in.” I assume the choice of telling the story through a community of characters’ lens is related to the collective aspect of any virus? What is your own analysis of this mise-en-scène choice?

Andrew: Contagion is remarkable for capturing the feeling of a pandemic — a slow, uneasy, almost banal sense of dread — then transforming it into a captivating experience. There are a number of interesting stylistic choices that contribute to this tone. The ensemble cast and networked narrative emphasize the qualities of the collective, rather than the powerful individual, which is very rare in Hollywood. Celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow and Kate Winslet are killed off unceremoniously: the former within nine minutes of the film starting, then given the indignity of a scalp removal in the cold light of an autopsy; the latter, assumed to be the film’s intrepid investigator, dies alone on a cot before being dumped in a mass grave. The cinematography borrows motifs from horror films (unnatural lighting and long, lingering shots of the unexpected) to give everyday objects a feeling of suspicion and danger. The bowl of peanuts, the touchscreen, the subway pole, the elevator button: these are transmission vectors given uncanny power through camerawork. Two types of title cards subtly ratchet up the stakes: cities and their populations denote the rapid spread (London, England population 8.6 million, Chicago, Illinois population 9.2 million, Tokyo, Japan population 36.6 million, etc.), while the timeline is marked by “Day 2,” “Day 3,” “Day 14,” and so on, in order to illustrate both how quickly the virus spreads but how important quick, decisive action is required. The propulsive, frantic soundtrack by long-time collaborator and electronic musician Cliff Martinez assists the film’s energetic pace, while also helping transport the viewer across such varied spaces and storylines. And the dry humor, under acknowledged in Soderbergh’s body of work, adds a bit of levity to an otherwise tense experience.

In The New York Times, Wesley Morris wrote an interesting article about his experience of re-watching Contagion recently. In particular, he says that in it, “Panic is a draw, and Soderbergh is the right guy to goose the dismay. He’s always practiced a filmmaking of neurotic compulsion.” Do you feel the same about this “neurotic compulsion” aspect of Soderbergh’s artwork?

Colin: I don’t necessarily agree with Morris here. I understand what he’s saying about compulsion, but I don’t see it as neurotic. If anything, Soderbergh is a workaholic polymath. He gives everything he has to a project and then moves on to the next one (or several) project(s). He is certainly intellectual here, but I think this is more aligned with the scientists and professionals in the movie — who he is clearly sympathetic to, and who are clearly the heroes — rather than typical protagonists such as Matt Damon (who is almost always asked to act against type in Soderbergh’s films). The paradox of Soderbergh seems to be that he is clearly a deep thinker about his subjects rather than the ‘deep feeler’ that we tend to associate with film artistry. The result are characterizations like Morris’s that define him as “neurotic” or “cold” about his art, where I think of Soderbergh’s work as a complete intellectual mastery of his subject matter combined with a close, artisanal approach to the cinematography, direction and editing.

Andrew: I do like Morris’ description of the film’s style though: “Contagion offers gymnastic catastrophe — it kicks, glides and throbs.” We can see this precision-crafted style throughout Soderbergh’s body of work: from revenge thrillers like The Limey and Out of Sight that elegantly glide back and forth through time, to the exuberant heists of the Ocean’s trilogy that unfold like clockwork, to social problem films like Traffic and The Laundromat that methodically document an issue across borders and communities, to crowd-pleasing genre films that provoke bodily pleasure from meticulously-crafted and performed sequences, such as the stripper saga Magic Mike, the MeToo-horror of Unsane, and the athletic action of Haywire.

In an interview with The Guardian in 2011, Soderbergh said that Contagion is “based on fear”. “It’s just a deadly virus, and viruses don’t have an ideology; you have an antagonist that can’t speak and with whom you can’t reason”, he said. I think this is a feeling that a lot of people are experiencing these days, and using a deadly virus as an antagonist is also just a great tool… for fiction! What can you say about Soderbergh’s view on the notion of fiction? How can his movies inform us about this deep confusion between fiction and reality which more and more people seem to feel nowadays?

Colin: The fact that millions seem to be turning to Contagion for facts about the coronavirus at precisely the moment when they can’t get any straight answers from their leaders. This is part of the reason why, for me, Jude Law’s campaign of disinformation is even worse than the virus itself. I think that this is exactly why we find ourselves in the situation that we’re in. The virus already took hold years ago when we stopped listening to experts and embraced ignorance instead.