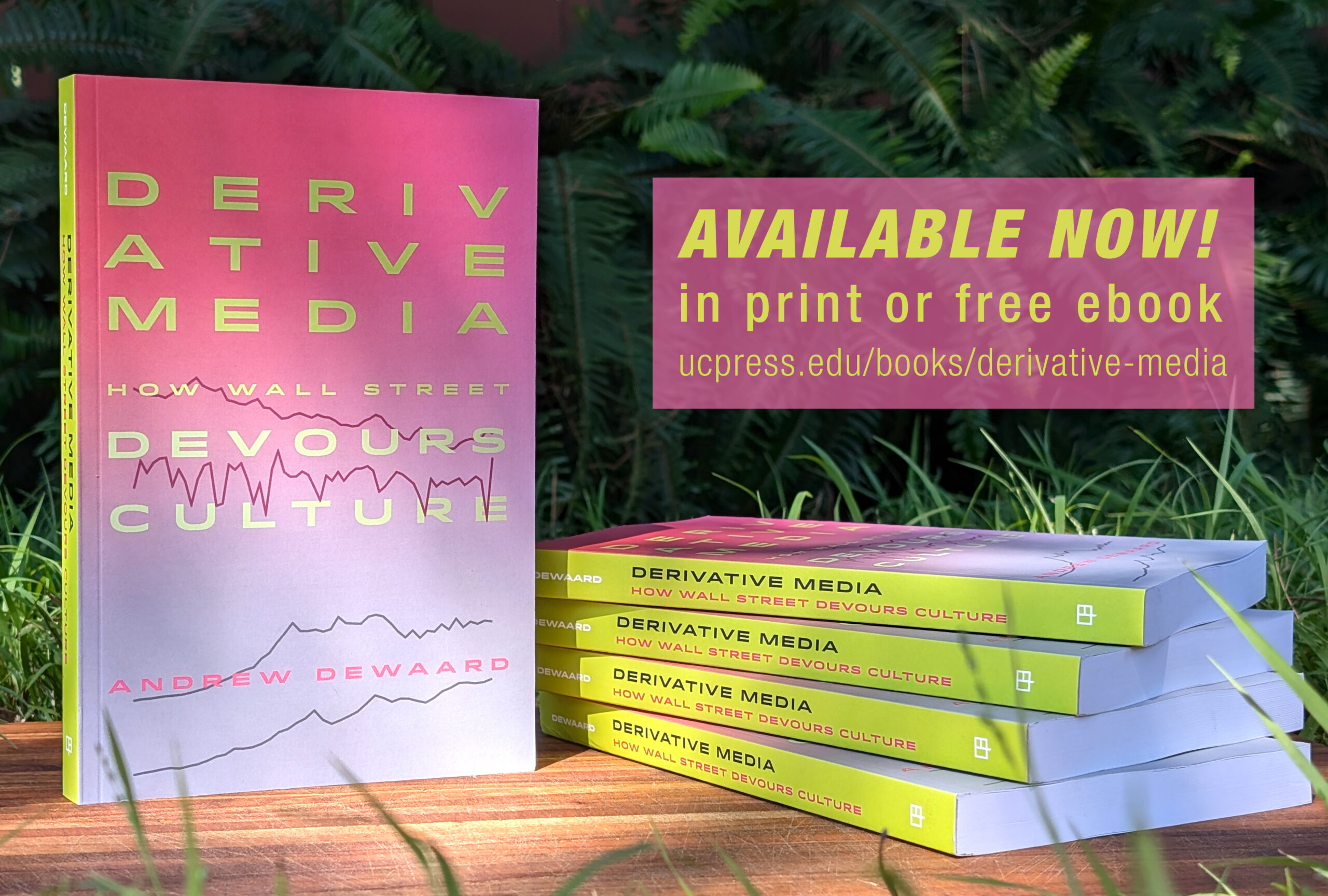

Steffen Hantke has quoted me in his essay entitled Tom LeClair’s Passing Trilogy: Recovering Adventure in the Age of Post-Genre, for Electronic Book Review. With the adventure genre having largely given way to the thriller in popular culture, and the distinct lack of adventure narratives in contemporary literature, Hantke looks at how LeClair’s brazen and ‘adventurous’ use of literary genres in his Passing Trilogy, employing both narrative and temporal deconstruction, negotiates a post-imperial world in which “postcolonial thought, in its widespread effects on contemporary Western culture, has thoroughly discredited the adventurer.” Hantke concludes his essay by considering my thoughts on ‘Post-Genre’ in the Editor’s Note I wrote for Cinephile Vol 4.1.

Much has been made in recent years of the death of genre, or at least its gradual weakening. Post-genre is the buzzword. Pointing out “Hollywood’s propensity for generic hybridity and overlap in his discussion of the action adventure film, Steve Neale makes the case that cinematic genres have started to move massively away from single distinct genres since the 1980s and ’90s (71) and toward a new polygeneric narrative that seems to transcend all inherited boundaries. This means that, by implication, there must have been an earlier period in which genres used to be, at least relatively speaking, distinct. In the Editor’s Note to a recent issue of Cinephile, Andrew deWaard suggests to read the sense of “perpetual aftermath” that dominates contemporary conceptions of genre not as a sign of its imminent demise but as an invitation for reconceptualization:

We can’t really leave genre behind anymore than we can abandon modernism or industry or structuralism – we’ve just mutated it to the point that it somehow feels new or different. Maybe we should start thinking ‘post’ as less of a temporal marker and more like computational logic. Let’s think of it as an upgrade: Genre 2.0, based on the same fundamental hardware, but with such forward-thinking software that it hardly warrants comparison. (2)

Tom LeClair’s approach to, and use of, genre in the Passing trilogy falls squarely into this model of what one might call “post-genre” for literary fiction. The hardware, as deWaard calls it, is still there, even though the software has been upgraded – to call it “forward-thinking” feels right as well. Readers are supposed to recognize the machinations of genre at work; the writing is intertextual enough, though never obtrusively so, to evoke the history of literary and cinematic adventure. The polygenericity of the trilogy, articulated as a series of shifts from one genre to another, does not undermine the validity of each single genre; instead, it follows an experimental logic. In his exploration of adventure, LeClair “tries out” genres; his moving on to the next is never a dismissal of the previous one. He is not out to abolish genres; does not exploit, consume, or use them up.

Hantke goes on to note that LeClair does not engage in satire, irony or pastiche — typical markers of postmodern genre play — before concluding his essay:

If the Passing trilogy is never patronizing or dismissive of adventure, it is an expression of LeClair’s generosity as a writer, as well as of the skill with which he sustains the tone in all three novels. But, more importantly, it is an expression of his recognition that adventure, as deWaard points out, is an enduring trope in Western culture. If it is simply not an option just to “leave it behind,” then to criticize it makes most sense if the critique is constructive. Adventure may be maligned as politically untenable, as escapism for the immature or uneducated; its hyperbolic pace and near-mythical iconography may seem absurd in a world of bourgeois security and moderation. But then, time and again, the reports of adventure’s imminent death have been greatly exaggerated. It deserves to be taken seriously because there is a place for adventure even in a culture that tells itself that there isn’t. What this place might be, Tom LeClair’s trilogy helps us to understand and imagine.

When I wrote that Editor’s Note, I was only really considering cinematic genre, so I appreciate Hantke applying my thoughts to literary genre as well. After all, the use of polygeneric narrative can be seen as something of a journey, the author taking the reader on a metatextual ride through a history of iconography, myth and archetype; adventure is a fitting study for this brave new generic world.